Campus walks: Walker Museum

With Cobb, Ryerson and Kent, buildings we have already roamed, Walker Museum, today simply called Walker Hall, also belongs to the core of the quads that was designed and built by the first leading architect of the University of Chicago, Henry Ives Cobb. Completed in 1893, Walker was originally a natural history museum.

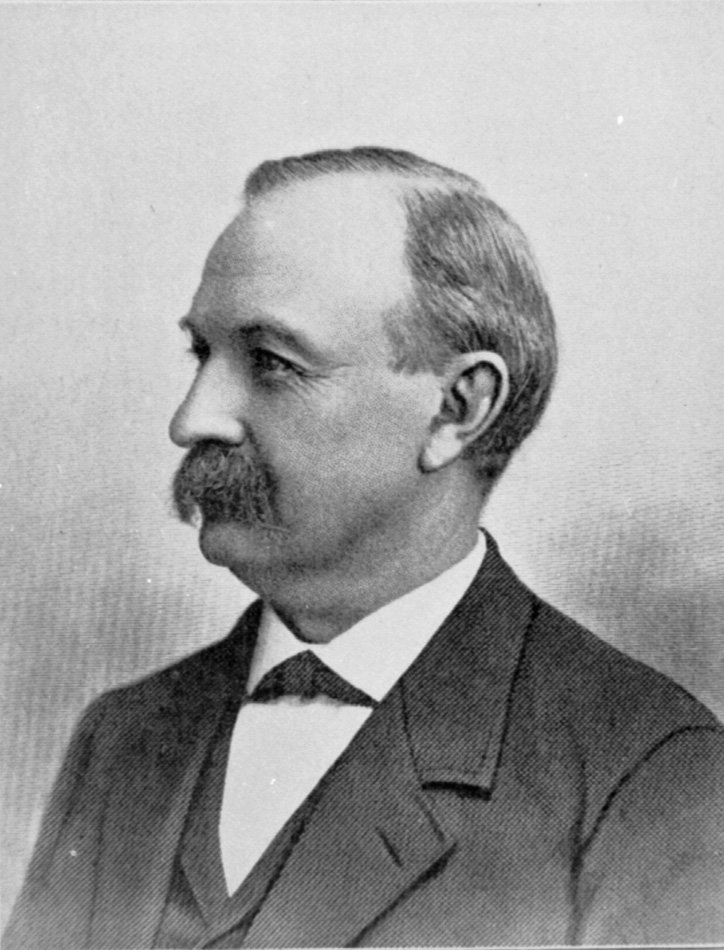

The building is named after George C. Walker (1835-1905), a real estate developer and a member of the first Board of Trustees of the new University of Chicago. How Walker got involved in the creation of the university is most interesting. After making the decision of starting a new institution, founders started finding the right location. The most obvious option was a place in the city, but during the early phase of the planning process Walker showed up and offered a property in the Morgan Park neighborhood. This is very south Chicago, down to 115th street.

Just a quick guide. Street numbers start in the Loop, the little core of the City of Chicago circumscribed by the CTA train lines. The Loop is thus very easy to find. This is the business center of the City, and here are the institutions including several theatres, operas and museums that earned Chicago the flattering label of ‘the cultural center of the United States.’ When you are in the Loop and headed to the south, leaving the Loop you walk (or run) in the 15th street area. Michigan and Indiana Avenues offer themselves to guide you all along your way to the university. In the Loop these long and straight streets are very close to the lake, but the lake takes a long left turn towards State Michigan, so when going south you get farther and farther from the lake shore. My suggestion, at 31st of 35th street you should take a left turn and then head back to south along Cottage Grove (this was my route on my morning run today) or, better, Lake Park Avenue. The university is situated between 55th and 60th streets, with some buildings, mainly dormitories and back-office facilities, even in 53rd and even in 61st. So, a site around 115th street would have been really far from the city, where the university was originally planned to be erected and started.

The site Walker offered was on 111th and Hoyne Avenue, and it already had a building on it. A sum of $25,000 was also in Walker’s package. Historians today think that Walker, at least partly, had an axe to grind. In the neighborhood of the new university he expected upper-class residents and businesses to infiltrate and increase the value of his properties. Finally, Trustees turned his offer down in favor of a site that Marshall Field donated to the university in the Hyde Park neighborhood, which back in the day was a township that the City of Chicago annexed recently. But Walker’s continuing enthusiasm about the university convinced the founders to get him in 1890 as a member of the first Board of Trustees. Walker thus became as one of the first major donors of the University of Chicago.

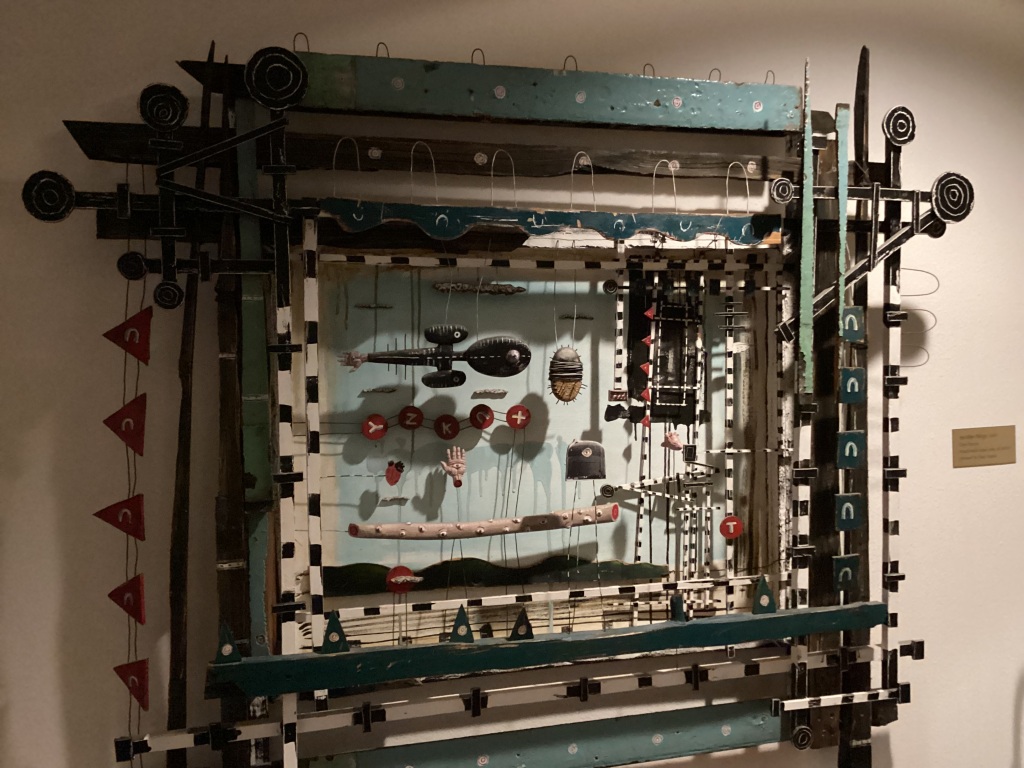

Walker worked really hard for the university, making the decision to involve him a fruitful step. Walker had family connections to Silas Cobb (Cobb was the father-in-law of Walker’s brother William), and Walker used these connections to convince Cobb in 1892 to make his donation, of which the University financed the building of Cobb Hall, the University’s first classroom building. Walker was also the one who persuaded his friend and fellow-businessman Sidney Kent to give $235,000 to cover the costs of a new chemical lab building. And Walker also made donations on his own right. In June 1892, he offered $130,000 to build a geology museum and laboratories. The building was completed in the following year, so Walker Museum opened its gates in 1893. Walker was dissatisfied with the outcome, though. The University was expanding so quickly and dynamically that departments were often in lack of sufficient office spaces and classrooms, so when the new museum building opened, some academic departments were relocated to find their new homes in the museum. Walker found this situation annoying and felt that easing the logistics for departments crowding out museum spaces faded the impact of his purposes and mission. In 1902 he was still arguing with fellow Trustees. Finally, he could convince President Harper to match the Museum’s intended and actual uses. Unfortunately, with time the new state of affairs turned out to be temporary only. Today Walker Museum is no longer a museum: this is the home to the offices of Dean of the Division of the Humanities, and on the two upper floors, the English Department. Only its remarkable open spaces preserve the memories of the former museum.